This article was originally produced for Decision Magazine, March 2019

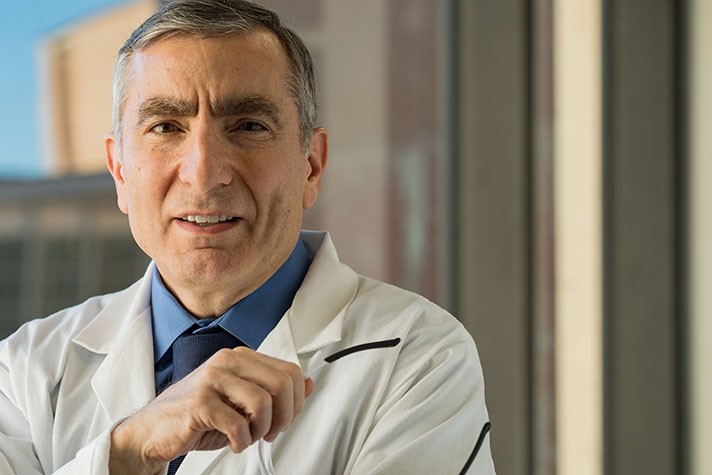

Acclaimed scientist, prolific researcher and innovative professor James Tour, Ph.D., is known for his work in the lab, on his computer and in the classroom. But as important and valuable as his scientific and academic contributions are, he would say that his most significant work is being done at home, in lunchrooms and on airplanes. And especially at the foot of his stairs before the dawn breaks each morning.

For 20 years, Tour has been teaching and leading research teams at Rice University in Houston, where he is a professor of chemistry, materials science and nanoengineering, and computer science. He has written hundreds of scholarly papers and is cited often and extensively by scientists worldwide.

His teams and the companies he has formed work across a number of disciplines in medicine. “We’re trying to make the lame walk, the blind see and the deaf hear,” he told Decision. “We’ve already made the deaf hear in certain kinds of deafness. We’re now working on the re-fusing of the optic nerve so we can do whole-eye transplants, which has never been done before. And we’re attempting to rebuild and re-fuse a separated spinal cord following spinal cord injuries, using nanomaterials.”

It’s Tour’s extended work in nanotechnology that has garnered intense attention. “We take molecules and build them up to be a nano-sized device, and we can then use that device for a certain function,” he explained in an interview with author and radio host Eric Metaxas. “One such device is a nanocar, which is a single molecule that has a chassis, axles, wheels and motor. You can park about 50,000 of them across the diameter of a human hair.”

It’s Tour’s extended work in nanotechnology that has garnered intense attention. “We take molecules and build them up to be a nano-sized device, and we can then use that device for a certain function,” he explained in an interview with author and radio host Eric Metaxas. “One such device is a nanocar, which is a single molecule that has a chassis, axles, wheels and motor. You can park about 50,000 of them across the diameter of a human hair.”

One of the vital applications of this research, Tour told Metaxas, is the fight against cancer. It’s long been a passion of his to help alleviate suffering. “We’ve taken these motorised vehicles, removed their axles and hooked on a peptide, which is a protein, which will find a certain cell in the body, for example a cancer cell and stick to it. And then we turn the motor on, and it drills a hole in that cancer cell in order to kill it.”

Tour and his older brother and sister grew up in what he describes as a secular Jewish home outside New York City. “I had a loving mother and father,” he said. “I always knew they loved me.”

Tour wanted to become a New York state trooper but couldn’t get into the academy because he was colour blind. He next considered studying forensic science. “But my father said, ‘Why don’t you just study chemistry generally and specialise after that,’ which was good advice.”

Religion was not discussed in the Tour household. “We never spoke negatively about Jesus, which is not the case in many Jewish homes,” Tour told Decision. “If I had come from a more traditional or Orthodox home, I would have been jaded in my view of Jesus. I had no view at all, negative or positive.”

The trajectory of Tour’s life changed when as a freshman at Syracuse University he heard the truth of the Gospel. In a conversation with a student in The Navigators, Tour was confronted by Matthew 5:27-28: “You have heard that it was said, ‘You shall not commit adultery.’ But I say to you that everyone who looks at a woman with lustful intent has already committed adultery with her in his heart.”

Addicted to pornography, Tour knew he was guilty. “It was the first indication to me that I was a sinner,” he said. “I thought you had to steal something or hurt somebody, but Jesus brought it right back to what I do in my heart. The student told me about how I could get to God through this Man Jesus Christ, who died and gave Himself for me.”

Tour wrestled with what he had heard. Later, in the quietness of his dorm room, he knelt on his knees, turned from his sins and asked God for forgiveness. “I felt this amazing relief of Him lifting the burden of my sin off of me.”

Since Nov. 7, 1977, Tour has been free of pornography. And his life has been transformed in myriad other ways.

From the outset, The Navigators and local church pastors helped him grow in Christ, teaching him how to pray and to read, study, memorise and meditate on the Bible—disciplines Tour continues to this day.

He is up every morning at 3:30 to invest two hours in God’s Word and in prayer—at the foot of his stairs. Then he heads to the gym for a rigorous 90-minute workout before going to class. He breaks at noon to pray for his students and the projects in which they’re involved.

Once at home, Tour is focused on his family. He and his wife, Shireen, met while washing and drying dishes after a dinner party at Syracuse. They married in 1982 and have four adult children—Ambreen, Sabrina, Josiah and Benaiah.

Sharing his faith with students and colleagues is another high priority, and God has honoured him. “My prayer is, ‘Lord, give me a person each week,’” Tour said. “I thank God that I see an average of one person coming to the Lord every week.”

“Rick had been antagonistic to the Christian faith,” Tour said. “We talked openly and honestly.” Tour gave Smalley some books, including titles by C.S. Lewis and Hugh Ross, an astrophysicist, apologist and author. He read them. “I invited Ross to campus, and Rick sat with him in my office for almost three hours, peppering him with questions.”

Smalley also attended a talk by Ross and came to know the Lord. “Rick was a powerful, influential man in the chemical community. He died of cancer a few years later, in 2005.”

But much of Tour’s ministry takes place at home and at church. He and Shireen host college students for lunch every week following the class he teaches at West University Baptist Church. Usually anywhere from 60 to 100 students cram into their home, overflowing to tables set up outside. He mingles with them and tells them about Jesus.

“Not only is there a weekly addition to the Kingdom,” says Senior Pastor Roger Patterson, “but there’s the exponential nature of what he’s doing. Take 20 years of doing this, pouring into some of the best and brightest, who are getting training and taking jobs all over the world. It’s immeasurable what God is doing on a global stage.”

When people commit their life to Christ, Tour asks local engineering consultant Mike Jackson and his Navigator team to disciple them. Tour and Jackson met eight years ago when Jackson helped launch The Navigators at Rice and Tour was its faculty sponsor.

Jackson relates how three doctors from a country in Asia once came to do research for a year at the nearby Texas Medical Centre. They visited Tour’s class at church, listened to him, interacted with him and prayed to receive Christ. Jackson spent months with the doctors and their families, nurturing their faith. They returned to their home country, and Jackson got to visit with two of them while on a recent business trip. They’ve remained faithful.

Tour’s unambiguous stand for Christ has made a deep impression on popular author and apologist Lee Strobel. In his book The Case for a Creator, he quotes Tour as saying, “Only a rookie who knows nothing about science would say science takes away from faith. If you really study science, it will bring you closer to God.”

“It’s one thing for a journalist like myself to report on what prominent experts say about Christianity,” Strobel told Decision. “It’s even more persuasive when a scientist of Dr. Tour’s unquestioned prominence makes his own well-researched conclusions known.”

Strobel added: “We need more people with Dr. Tour’s sincere devotion to Christ, his passion to help people, and his sharp scientific mind to be an influence for Christ.”

The Scripture quotation is taken from The Holy Bible, English Standard Version.

Richard Greene is a former Decision assistant editor. He recently retired as a senior editor at Samaritan’s Purse in Boone, N.C.